e-Learning Ecologies MOOC’s Updates

Collaborative and Individual Intelligence: The Case for Assessments

This week’s content focuses on individual-traditional forms of intelligence as compared to collaborative-social intelligence and inheritance, to name but two of the reading’s and the lessons’ motifs. These latter affordances advanced, at the least in terms of efficiency, by newer media and “digital ecology spaces” (Video 5B) notwithstanding, there are some points from this week’s lessons that need further definition or, really, further clarification.

To begin with, there exists a strong case to be made for “individual” intelligence, artifacts, and assessments. To make clear, however, “individual” here does not mean that a learner takes credit for so-called “original” ideas and does not rely on the shoulders of giants; it simply means that the activity, project, or assessment does not involve him or her directly working with peers in the production of the artifact.

That said, because I believe that learning activities and projects should be collaborative—comments from peer reviews, professional tutors, and the instructor—I will focus on assessments, which take on a variety of forms:

- online or paper-and-pen un/proctored

- interactive videos

- formative and summative

- portfolios of work

- essays

- traditional multiple-choice, T/F, matching, etc.

- polling (using mobile devices)

- video-and scenario-based

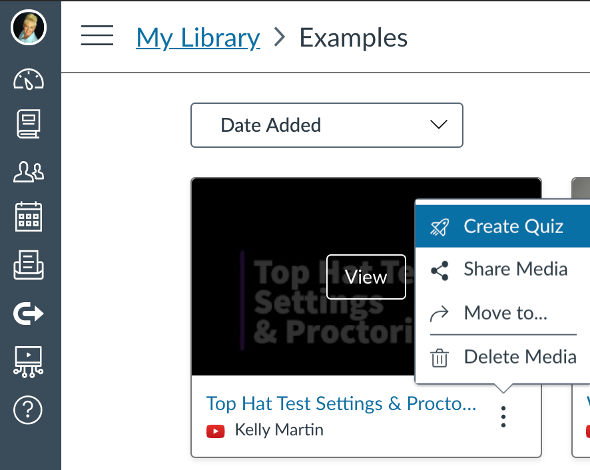

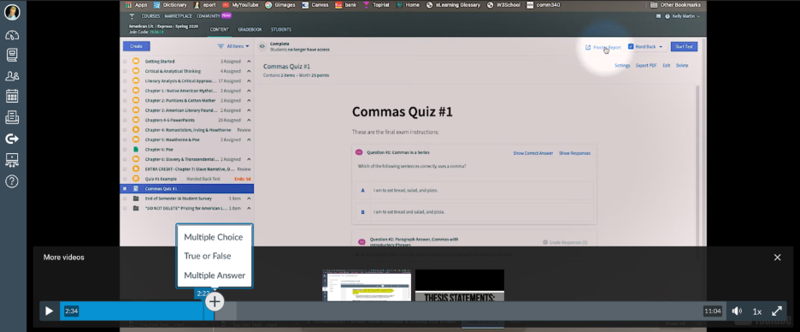

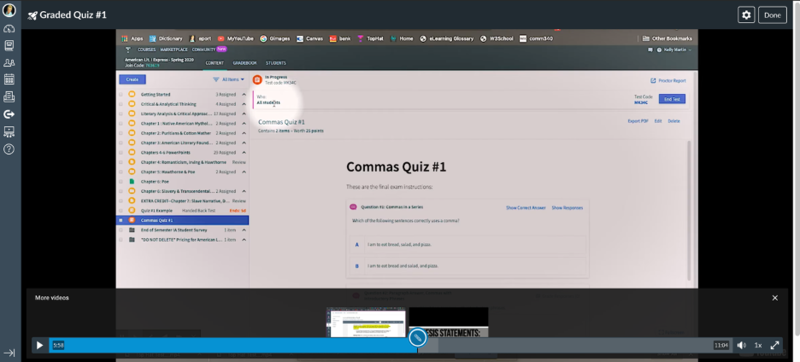

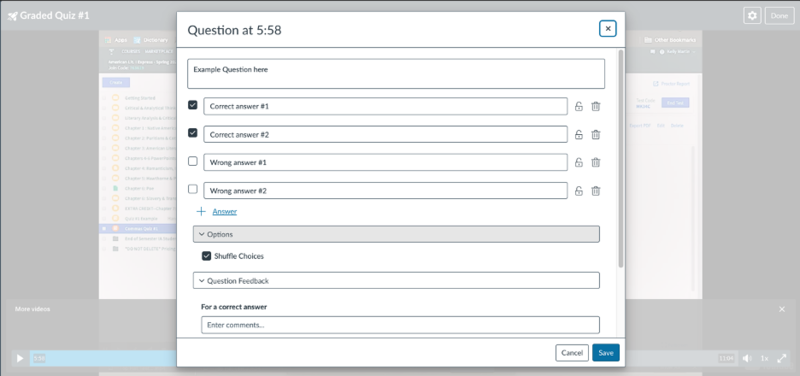

The following are screenshots or video demonstrations of some progressive online assessments developed with different platforms or apps:

Using Canvas Studio to Create Interactive Video Assessments:

Using the Kahoot App for In-Class Polling and Formative Assessment:

Using Top Hat Remote Proctoring Tool for Assessment:

Using Adobe Captive to Create Interactive Video Assessments:

Part II

To a degree, all knowledge is collective because we draw upon our own and others’ multiple experiences, artifacts, and perspectives to then process new information, to make sense of new knowledge and experiences, and to create our own unique composites and storehouses of mental models. Nevertheless, individual intelligence and assessments are of value.

For example, in Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning the authors write of standardized tests and acknowledge their pitfalls, one of the most common being “teaching to the test,” but they also argue that (individual) tests actually advance learning. Their argument rests on a rethinking—a paradigm shift, if you will—of testing. They write, “If we stop thinking of testing as a dipstick to measure learning—if we think of it as practicing retrieval of learning from memory rather than ‘testing’, we open ourselves to another possibility: the use of testing as a tool for learning” (19, emphasis in original). This idea of testing as an instrument of learning is the authors’ response to a call of action: “[W]hat we really ought to ask is how to do better at building knowledge and creativity [emphasis in original]” (18).

From Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel’s extended argument for reimagining the nature and purpose of testing, we learn the importance of individual intelligence and of harnessing the power of memory, both of which grow from foundational and factual knowledge. In fact, these authors liken mastery of a knowledge domain or a skillset to a construction site for the building of a new house (18); the concrete materials, the brick, the wood, nails, and more are first delivered, and from here, the foundation can be poured and the structure constructed. The authors’ point is that “Mastery in any field . . . is a gradual accretion of knowledge, conceptual understanding, judgment, and skill” (18).

They further argue that “. . . without knowledge, you don’t have the foundation for higher-level skills” (18); Robert Sternberg, a psychologist, whom the authors quote on page 18 and whom I paraphrase here, claims that if we do not know something, we cannot apply, analyze, synthesize, or evaluate that something and its significance to or implications for new and emerging knowledge, skillsets, experiences, media and technologies, and to other, even greater life facets and to those of ontology and the metaphysical realms.

Indeed, as Brown, Roediger, and McDaniel note, we must appreciate that testing is an unfortunate political hotspot for educators, parents, students, and learning science experts. Laypeople and educational practitioners and theorists argue (and as also paraphrased by the authors) that teaching to the test diminishes students’ creative skillsets and often detracts from “real” learning (which still, for too many, takes the form of didactic pedagogy).

In contrast, testing (whether online or on paper), memory and retrieval, and foundational knowledge—that when collectively considered are a manifold of robust elements of teaching and learning—actually make knowledge construction, the process of encoding, and the process of developing mental models more efficient, thus making us better performers, more successful, and stronger learners overall; “[r]retrieval ties the knot for memory . . . and we’ve long known that the act of retrieving knowledge from memory has the effect of making that knowledge easier to call up again in the future” (28). Simply put, “practicing retrieval makes learning stick,” and this concept is known as the testing or retrieval-practice effect (28).

Part III

Revisiting my introductory points, I want to particularly ensure that one point is very pronounced: in no way am I dismissing the efficacy of collaborative-social learning and intelligence; I am simply arguing that individual assessments should not be unduly dismissed. After all, memories are specific to each one of us. To be reminded of this point, we only need to look to the validity of eyewitnesses’ court testimonies of a crime or to a set of siblings’ differing memories of when they simultaneously beheld the grandeur of the Grand Canyon for the first time while on a summer vacation with their parents.

Individual assessment is not, in and of itself good or bad, just as technology and digital media are not. We must remember that they, old or new, are neutral. Nevertheless, digital is more accommodating to representing conceptual and logical networks of information, thus making more visible the multiple shoulders on which numerous giants stand. In turn, this new media amalgam of affordances more efficiently inspires and highlights the possibilities of dialectical pedagogy and for collaborative learning.

It is, quite frankly, time to recognize and reconceptualize the nuances and shades—the grey area or middle ground—of digital epistemic dimensions: ones in which individual and collaborative activities, old and new technologies and media, foundational and higher-order skills, and conventional and progressive pedagogies converge. We need to stop pitting one against the other, thereby creating a false dichotomy of thinking about teaching and learning.

Works Cited

Brown, Roediger III, and McDaniel. Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. Harvard UP, 2014.