e-Learning Ecologies MOOC’s Updates

SOVC & First-Generation Student Communities

Priest, Saucier, and Eiselein (2016) frame learning as “socialization and identity shaping process in which learners gain knowledge and skills contextualized, and legitimized, by their communities” (p.361)

This made me think about my experience as a first-generation student navigating new waters for the first time. Luckily, I was chosen as a participant in an all-expenses paid overnight visit program at one of the colleges on my list as a senior in high school. I had the opportunity to learn about the social, academic, and extracurricular opportunities that would be afforded to me if I were to accept my offer to this specific institution. It was, for all extents and purposes, a great way to recruit first-generation college students who would otherwise not be able to afford the trip to visit and “experience” the college (and whose wealthy counterparts are able to do so without much inconvenience). Therefore, more than a recruiting tool, this was a way to build equity in a system that otherwise would not make room for it.

Now, in the 21st century, in the times of COVID-19 specifically, I think about how these types of “Multicultural Visit Programs” or “First Generation Student Bridge Programs” will be affected. At conferences, I’ve heard about the value of virtual tours, which allow students an opportunity to put themselves in the shoes of a student at that school in a virtual setting - which is better than not having any sense of it at all.

That leads me to my next question on the matter of virtual socialization experiences in a first-generation, low income- student context: How do we build and model “community” for first-generation students in virtual spaces? For so long, we were able to provide these experiences to students to “prime” them for their first prospective year at the prospective institution. But now, in a global pandemic, students are having to limit their expectations of their choices because of an inability to make informed decisions - something that these in-person bridge programs/recruiting programs attempt to provide.

Building an in-person community as a means of providing a welcoming environment for underrepresented students in new contexts and attempting the same endeavor in a virtual space require similar foundations but different practices.

I’ve noticed in my work and relationships with TRIO program partners (TRIO programs are federally funded college access programs that support first-generation students) - insert link to TRIO websites, directors and advisors in these times of COVID-19 are using social media as a means of interacting with their students and checking in for academic reasons, but most important, also as a means of creating community with these students. Building a sense of community in TRIO programs has become a new challenge for them in the virtual world; they, like many of us, have become accustomed to building relationships in-person (both peer-to-peer and peer-to-mentor), and relying on this sense of community to gain students’ trust and establish mentorship opportunities to encourage persistence in education (and in life).

One major challenge in building a virtual community is the separation-- literally being distant from others --- that is implicit in a virtual community “has a tendency to reduce the sense of community, giving rise to feelings of disconnection (Kerka 1996), isolation, distraction, and lack of personal attention (Besser & Donahue, 1996; Twigg, 1997).http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/79/153

The disconnect has been affirmed so much so in research surrounding virtual community building that it has its own acronym - SOVC (sense of virtual community). After some research, I’ve learned that the idea of what makes up not only the discourse of SOVC but also the practices supporting is up to contentious debates.

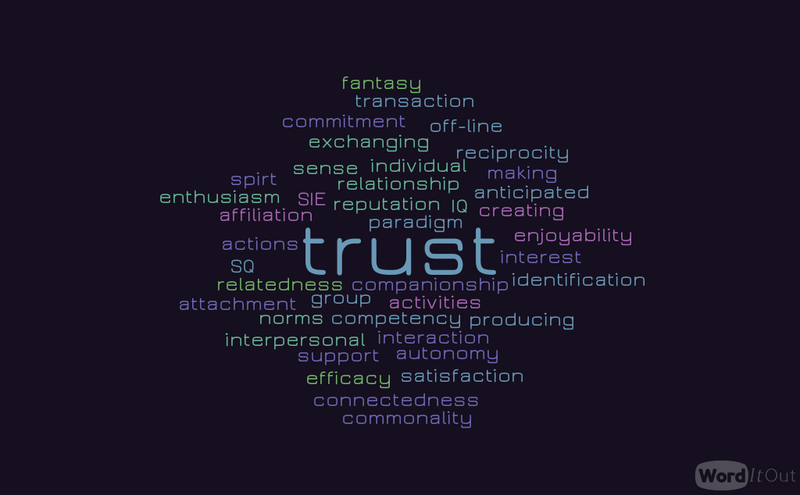

I thought that a cool way of summarizing my research on the characteristics that create a SOVC with a word cloud, since there are a variety of terms that are represented throughout the discourse on the matter.

I thought that a cool way of summarizing my research on the characteristics that create a SOVC with a word cloud since there are a variety of terms that are represented throughout the discourse on the matter.

WIth word clouds, the more often a term comes up, the more space it takes up on the cloud. In this case, it is clear that “trust” comes up the most as a defining characteristic of building a sense of virtual community. Other patterns in defining characteristics include a sense of being related to one another (connectedness, identification, attachment, interaction, commonality, transaction, companionship, reciprocity) as well as a sense of ease and entertainment (enjoyability, satisfaction, efficacy, enthusiasm, spirit).

Most importantly, and going back to the beginning of this update, I learned that SOVC is integral to maintaining continuity and investment in an online community. Therefore, when applying this lens of SOVC to a first-generation student audience (wherein receiving support while navigating new territory is pivotal to success), I wondered if I could find an example of SOVC in action. And I did!: The First Year Learning Communities at City Tech in New York.

To learn more about this program check out the work that they do to create first-generation narratives and community with blended engagement practices.

I thought that the FYLC at City Tech provided a wonderful example of how institutions, such as TRIO programs, can begin to reimagine the types of interventions that can take place to build a sense of virtual community with first-generation students. What stands out the most in this project is not only the SOVC but also the effects of collaborative learning on students’ sense of their own personal narratives. Thus, I believe that building a strong sense of SOVC for first-generation students starts with this transformative approach to knowledge sharing as a means of recreating our own narratives. It is no surprise, then, that college access leaders in TRIO programs are turning to social media as a form of engagement with students - here, identity formation is in constant flux, and mentors are meeting students in a space that is inherently vulnerable, self-conscious, and ripe for innovation and renovation.

Works Cited:

Priest, K.L., Saucier, D.A., & Eiselein, G. (2016). Exploring students’ experiences in first-year learning communities from a situated learning perspective. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 28(3) 361-371.