Assessment for Learning MOOC’s Updates

Standards-Based and Alternative Practices of Assessment (Admin Update 3)

Standards-based assessment allows the possibility that everyone in a certain level of education or in the same class can succeed. For the underlying principles, see:

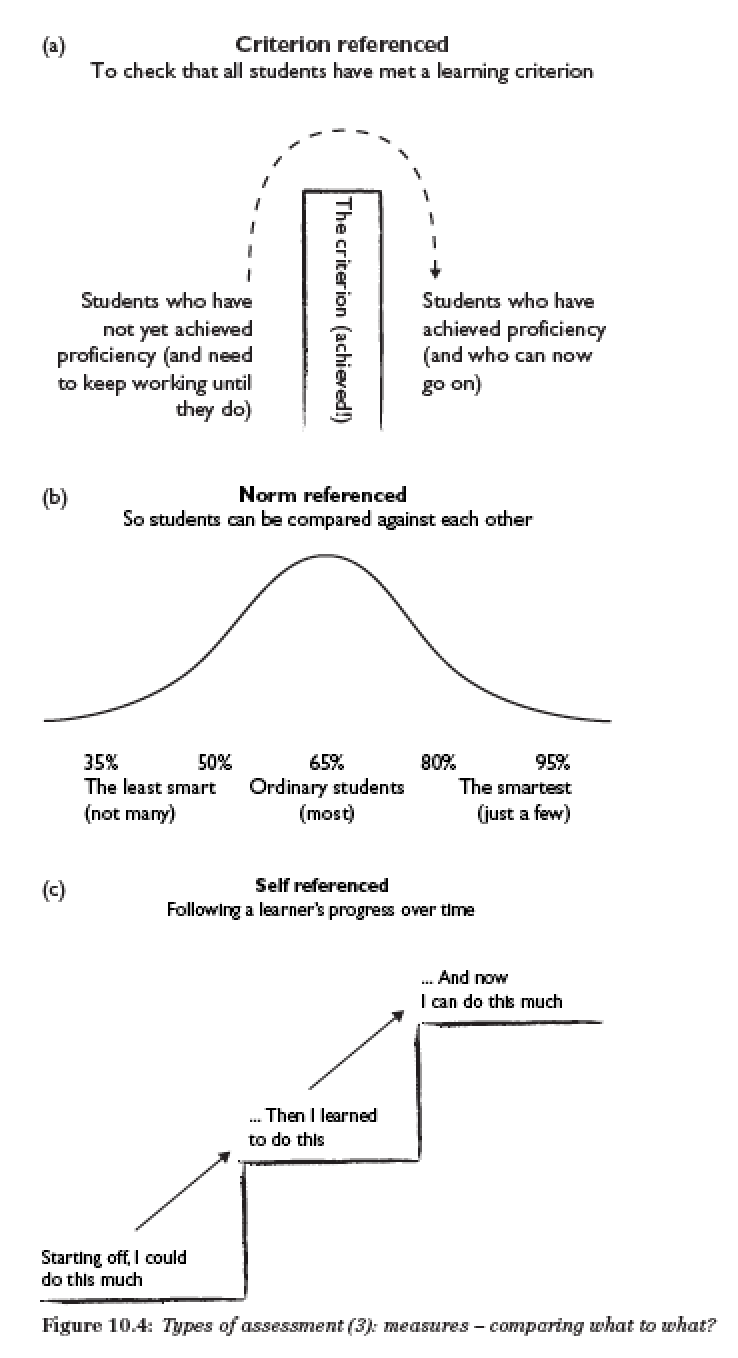

Criterion referenced, norm-referenced and self-referenced assessments have fundamentally different logics and social purposes. In the following image from Chapter 10 of our New Learning book, we attempt to characterize the different logics. But what are the different social assumptions?

Comment: What are the social assumptions of each kind of assessment? What are the consequences for learners? For better and/or for worse, in each case?

Make an Update: Find an example of an alternative form of assessment. Describe and analyze it.

ASSESSING INTELLIGENCE VERSUS KNOWLEDGE.

Testing intelligence measures students’ ability to think critically and solve problems, while testing for knowledge evaluates what they have learned from the curriculum. For instance, as a Grade 9 Filipino teacher, testing intelligence might involve presenting an unfamiliar poem and asking students to interpret its meaning or identify underlying themes, which assesses reasoning and comprehension skills. In contrast, testing for knowledge could involve asking students to define “talinghaga” or enumerate the characteristics of a sonnet, which checks their mastery of previously taught concepts. Intelligence testing is most appropriate when gauging analytical thinking and adaptability, while knowledge testing is best for verifying content retention and understanding.

Example of an Intelligence Test

Raven’s Progressive Matrices (RPM)

This is a widely used nonverbal intelligence test designed to measure abstract reasoning and problem-solving ability. It consists of a series of visual patterns with a missing piece, and the test-taker must choose the correct piece from multiple options to complete the pattern.

How It Works

The patterns become progressively more complex as the test goes on.

It does not rely on language or prior knowledge, making it suitable for diverse populations.

It primarily assesses fluid intelligence—the ability to reason and solve new problems.

Strengths

Culture-fair: Minimal language requirements reduce bias.

Measures reasoning ability: Good for assessing cognitive potential rather than learned content.

Quick and easy to administer: Often used in educational and employment settings.

Weaknesses

Limited scope: Focuses on abstract reasoning, not practical or verbal skills.

Test anxiety and unfamiliarity: Students may struggle if they have never encountered such tasks.

Not curriculum-based: Cannot measure subject mastery or specific knowledge.

Different Types of Assessments

Different types of assessments come with different social assumptions, which can help learners or cause problems for them. Traditional tests, like standardized tests, assume that all students learn the same way and can show their knowledge through the same set of questions. This can help teachers compare results and see who needs support, but it can also hurt students who struggle with test pressure, who learn differently, or who did not have the same opportunities to study the material. Intelligence tests often assume that a person’s thinking ability can be measured with a single score. This can help identify learning needs or strengths, but it can also make some students feel labeled or judged, as if their intelligence never changes. These assumptions can lead to both good and bad consequences: some students may get extra help or confidence, while others may feel limited, stressed, or misunderstood. For the update, an example of an alternative assessment is a portfolio assessment, where students collect their work—like projects, writing, drawings, or other assignments—over time to show what they have learned. This type of assessment lets students show their skills in different ways, not just through tests. One strength is that it gives a fuller picture of a student’s learning and allows creativity. It also reduces stress because it does not depend on a single test day. A weakness is that it takes more time for teachers to review and can be harder to score fairly since it involves personal judgment. Even with these challenges, portfolio assessments can help students show what they really know and can do in a more natural and meaningful way.

Different assessment types carry different social assumptions about what learning is and how it should be demonstrated. These assumptions shape how learners are evaluated—and how they see themselves.

1. Standardized / Summative Assessments

Social assumptions:

Learning can be measured objectively through uniform tasks.

All students should reach the same benchmarks at the same time.

Scores reflect ability, effort, or school quality.

Consequences for learners:

Better: Provides consistency, identifies large‑scale trends, and highlights systemic gaps.

Worse: Can create anxiety, narrow the curriculum, and disadvantage learners whose strengths are not captured by timed, test‑based formats.

2. Formative / Classroom-Based Assessments

Social assumptions:

Learning is ongoing and best understood through continuous feedback.

Teachers know their learners’ contexts and can adjust instruction accordingly.

Mistakes are part of growth.

Consequences for learners:

Better: Reduces pressure, supports improvement, and builds confidence through timely feedback.

Worse: Can be subjective if criteria are unclear; teacher bias may unintentionally influence results.

3. Alternative / Authentic Assessments

Social assumptions:

Learning is diverse, contextual, and demonstrated through real‑world tasks.

Students should show understanding through performance, creation, or application—not just recall.

Multiple forms of evidence provide a fuller picture of ability.

Consequences for learners:

Better: Encourages creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and real‑life problem‑solving.

Worse: Time‑consuming, harder to standardize, and may challenge learners who need more structure.

✅ Update: Example of an Alternative Form of Assessment

Example: Performance Task Assessment

A performance task requires students to apply knowledge and skills to create a product, solve a real‑world problem, or demonstrate a process. Instead of answering test questions, learners perform their understanding.

How it works

Students are given an authentic task (e.g., designing a fitness plan, creating a cultural presentation, conducting an experiment, choreographing a dance, or solving a community issue).

Clear rubrics guide expectations.

Students produce an output or performance and often include a reflection explaining their decisions.

Strengths

Authentic application: Measures how students use knowledge, not just recall it.

Engaging and meaningful: Connects learning to real-life contexts.

Inclusive: Allows different strengths—creativity, communication, collaboration, problem‑solving—to emerge.

Deep learning: Encourages analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

Weaknesses

Time‑intensive: Requires planning, resources, and teacher facilitation.

Scoring challenges: Needs well‑designed rubrics to ensure fairness.

Varied outputs: Quality may depend on access to materials or support outside school.

Teacher expertise: Effective implementation requires strong assessment literacy.

@JohnOpre In the context of Assessment of Learning, intelligence testing and knowledge testing are shaped not only by educational goals but also by social assumptions. These assumptions influence how learners are viewed and how their abilities are interpreted. Understanding these underlying beliefs is important because they have significant consequences for learners’ opportunities, self-esteem, and future academic experiences.

Social Assumptions Behind Intelligence Testing

Intelligence testing is often based on the assumption that intelligence is an innate, fixed, and measurable trait. Society tends to believe that a single score, such as an IQ number, can summarize a person’s thinking ability and predict future success. This creates the belief that some learners are naturally “smart,” while others are inherently less capable. Another social assumption is that intelligence is universal and can be assessed fairly across different cultures, backgrounds, and languages, even though many intelligence tests reflect cultural norms, experiences, and values of certain groups.

Consequences for Learners (Intelligence Testing)

The consequences of these assumptions can be both positive and negative. On the positive side, learners who score high may gain access to enrichment programs, scholarships, or advanced learning opportunities. However, negative consequences can be harmful. Learners who score low may be labeled as less capable, which can affect their confidence and motivation. These labels can follow them through their schooling, influencing teacher expectations and limiting access to academic opportunities. Because intelligence tests often contain cultural biases, learners from less privileged backgrounds may be unfairly judged, resulting in social inequality being reinforced rather than reduced.

⸻

Social Assumptions Behind Knowledge Testing

Knowledge-based assessments are grounded in the assumption that learning is primarily the accumulation of information and mastery of skills taught in school. Society often assumes that students who perform well on tests are hardworking, responsible, and successful learners, while those who perform poorly are lazy or inattentive. There is also an assumption that all students have equal access to learning resources, quality teaching, and supportive environments—conditions that are not always true.

Another assumption is that standardized tests or classroom exams are objective and fair measures of learning, even though they often favor students who have stronger test-taking skills, language proficiency, or better support at home.

Consequences for Learners (Knowledge Testing)

The consequences of these assumptions also affect students in powerful ways. High-performing students are often rewarded with praise, recognition, and opportunities, reinforcing their sense of competence. For students who struggle, repeated low scores can lead to shame, frustration, and loss of motivation. They may begin to see themselves as “slow learners,” even if their difficulties come from external factors such as limited resources, poor instruction, or language barriers.

Knowledge-focused assessments can also narrow the curriculum when teachers feel pressured to “teach to the test,” reducing creativity, critical thinking, and meaningful learning experiences for all students. Learners may come to value memorization over understanding, which limits deeper learning.

@JohnOpre In the context of Assessment of Learning, intelligence testing and knowledge testing are shaped not only by educational goals but also by social assumptions. These assumptions influence how learners are viewed and how their abilities are interpreted. Understanding these underlying beliefs is important because they have significant consequences for learners’ opportunities, self-esteem, and future academic experiences.

Social Assumptions Behind Intelligence Testing

Intelligence testing is often based on the assumption that intelligence is an innate, fixed, and measurable trait. Society tends to believe that a single score, such as an IQ number, can summarize a person’s thinking ability and predict future success. This creates the belief that some learners are naturally “smart,” while others are inherently less capable. Another social assumption is that intelligence is universal and can be assessed fairly across different cultures, backgrounds, and languages, even though many intelligence tests reflect cultural norms, experiences, and values of certain groups.

Consequences for Learners (Intelligence Testing)

The consequences of these assumptions can be both positive and negative. On the positive side, learners who score high may gain access to enrichment programs, scholarships, or advanced learning opportunities. However, negative consequences can be harmful. Learners who score low may be labeled as less capable, which can affect their confidence and motivation. These labels can follow them through their schooling, influencing teacher expectations and limiting access to academic opportunities. Because intelligence tests often contain cultural biases, learners from less privileged backgrounds may be unfairly judged, resulting in social inequality being reinforced rather than reduced.

⸻

Social Assumptions Behind Knowledge Testing

Knowledge-based assessments are grounded in the assumption that learning is primarily the accumulation of information and mastery of skills taught in school. Society often assumes that students who perform well on tests are hardworking, responsible, and successful learners, while those who perform poorly are lazy or inattentive. There is also an assumption that all students have equal access to learning resources, quality teaching, and supportive environments—conditions that are not always true.

Another assumption is that standardized tests or classroom exams are objective and fair measures of learning, even though they often favor students who have stronger test-taking skills, language proficiency, or better support at home.

Consequences for Learners (Knowledge Testing)

The consequences of these assumptions also affect students in powerful ways. High-performing students are often rewarded with praise, recognition, and opportunities, reinforcing their sense of competence. For students who struggle, repeated low scores can lead to shame, frustration, and loss of motivation. They may begin to see themselves as “slow learners,” even if their difficulties come from external factors such as limited resources, poor instruction, or language barriers.

Knowledge-focused assessments can also narrow the curriculum when teachers feel pressured to “teach to the test,” reducing creativity, critical thinking, and meaningful learning experiences for all students. Learners may come to value memorization over understanding, which limits deeper learning.

Standardized testing can provide students with clear goals and expectations for what they need to learn at each grade level. When students know there's a test coming, it can motivate some of them to study and take their learning seriously. The tests also help identify students who are falling behind early enough that schools can provide extra support through tutoring or intervention programs. For students in under-resourced schools, standardized tests can sometimes reveal inequities that might otherwise go unnoticed, potentially leading to more funding or resources. Additionally, high-performing students may gain recognition for their achievements, and strong test scores can open doors to advanced placement classes, gifted programs, or scholarships. The structured preparation can also teach students valuable test-taking skills—like time management, reading instructions carefully, and staying calm under pressure—that they'll need for college entrance exams and professional certifications later in life.

On the other hand, the negative consequences for learners are often more profound and lasting. Students experience significant stress and anxiety around high-stakes testing, which can harm their mental health and actually impair their performance on test day. Those who struggle with standardized tests—even if they're intelligent and capable in other ways—may internalize the message that they're not smart, damaging their self-confidence and motivation to learn. Students miss out on enriching educational experiences because so much classroom time is devoted to test prep rather than hands-on projects, creative exploration, or developing critical thinking skills. The narrow focus on reading and math means less time for subjects like art, music, physical education, and social studies that make school engaging and develop well-rounded individuals.

For this update, I examined how the National Achievement Test (NAT) is implemented in Philippine schools. The NAT is a nationwide standardized assessment given to specific grade levels to measure students’ mastery of key learning areas. It follows a fixed format, uses multiple-choice items, and is administered under strict testing conditions to ensure consistency across schools.

One strength of the NAT is that it provides reliable, large-scale data that helps DepEd identify learning gaps and monitor overall educational performance. It also guides schools in improving instruction based on competency trends. However, its weaknesses include test anxiety among learners, the risk of teaching “to the test,” and the limited scope of multiple-choice items, which may not fully capture higher-order thinking or real-world skills.

For this update, I examined how the National Achievement Test (NAT) is implemented in Philippine schools. The NAT is a nationwide standardized assessment given to specific grade levels to measure students’ mastery of key learning areas. It follows a fixed format, uses multiple-choice items, and is administered under strict testing conditions to ensure consistency across schools.

One strength of the NAT is that it provides reliable, large-scale data that helps DepEd identify learning gaps and monitor overall educational performance. It also guides schools in improving instruction based on competency trends. However, its weaknesses include test anxiety among learners, the risk of teaching “to the test,” and the limited scope of multiple-choice items, which may not fully capture higher-order thinking or real-world skills.

For this update, I examined how the National Achievement Test (NAT) is implemented in Philippine schools. The NAT is a nationwide standardized assessment given to specific grade levels to measure students’ mastery of key learning areas. It follows a fixed format, uses multiple-choice items, and is administered under strict testing conditions to ensure consistency across schools.

One strength of the NAT is that it provides reliable, large-scale data that helps DepEd identify learning gaps and monitor overall educational performance. It also guides schools in improving instruction based on competency trends. However, its weaknesses include test anxiety among learners, the risk of teaching “to the test,” and the limited scope of multiple-choice items, which may not fully capture higher-order thinking or real-world skills.

For this update, I examined how the National Achievement Test (NAT) is implemented in Philippine schools. The NAT is a nationwide standardized assessment given to specific grade levels to measure students’ mastery of key learning areas. It follows a fixed format, uses multiple-choice items, and is administered under strict testing conditions to ensure consistency across schools.

One strength of the NAT is that it provides reliable, large-scale data that helps DepEd identify learning gaps and monitor overall educational performance. It also guides schools in improving instruction based on competency trends. However, its weaknesses include test anxiety among learners, the risk of teaching “to the test,” and the limited scope of multiple-choice items, which may not fully capture higher-order thinking or real-world skills.

Standardized, or summative, assessments are socially assumed to provide objective, universal metrics for accountability and predicting future success, leading to better consequences like clarifying essential academic standards and revealing systemic achievement gaps, but worse consequences like severe student anxiety, curriculum narrowing (teaching to the test), and unfairly penalizing students from disadvantaged backgrounds due to their strong correlation with socioeconomic status. Conversely, formative (classroom-based) assessments are assumed to prioritize individual growth and contextual learning, yielding better results such as enhanced student self-reflection, reduced test anxiety through low-stakes environments, and targeted instructional intervention, but they risk worse consequences like subjective grading inconsistencies and the potential for grade inflation if not properly aligned with external academic consistency.

Intelligence tests often assume that thinking skills can be measured the same way for everyone, even though culture and language affect performance. Knowledge tests assume that everyone had equal access to learning the material. Both assumptions can be risky. For learners, intelligence tests can create labels—sometimes helpful for support, but sometimes limiting. Knowledge tests can motivate learning, but they can also punish students who didn’t get the same opportunities. So in both cases, the consequences can be positive or negative depending on how fairly the tests are used.