Assessment for Learning MOOC’s Updates

Select and Supply Response Assessments (Admin Update 2)

Item-based, standardized tests have epistemological and social bases.

Their epistemological basis is an assumption that there can be right and wrong answers to the things that matter in a discipline (facts, definitions, numerical answers to problems), and from the sum of these answers we can infer deeper understanding of a topic or discipline. (You must have understood something if you got the right answer?) Right answers are juxtaposed beside 'distractors'—plausible, nearly right answers or mistakes it would be easy to make. The testing game is to sift the right from the (deceptively) wrong.

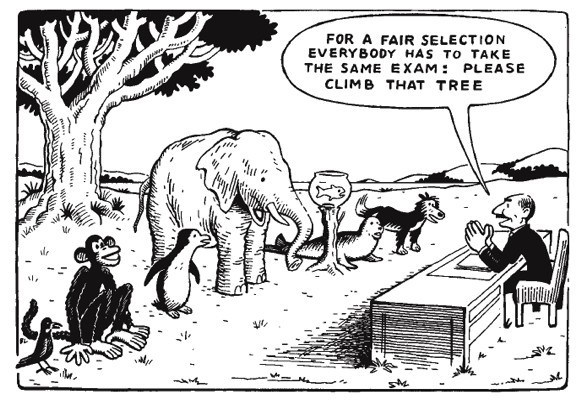

The social basis of item-based tests is the idea of standardization, or tests which are administered to everyone in the same way for the purposes of comparison measured in terms of comparative success or failure.

Psychometrics is a statistical measurement process that supports generalizations from what is at root survey data. (An item-based test is essentially, a kind of psychological survey, whose purpose is to measure knowledge and understanding.)

Today, some standardized tests, such as PISA and TIMMS aim to evaluate higher order disciplinary skills.

Comment: When are standardized tests at their best? And/or worst?

Make an Update: "Parse" a standardized test. Or describe the implementation of a standardized test in practice. What are its strengths and weaknesses?

The Strengths and Weaknesses of Standardized Testing

Standardized tests are at their best when they are used to measure learning in a fair, consistent, and organized way, such as when schools want to check whether students have met certain grade-level expectations or when programs need an objective way to compare applicants. They work well when the test is clearly written, based on what students were actually taught, and when everyone has an equal chance to prepare. They are also helpful for identifying gaps in instruction, tracking progress over time, and making large-scale decisions, like curriculum changes. However, standardized tests are at their worst when they become the main source of pressure for students and teachers, when they encourage memorization instead of real understanding, or when they are used to judge intelligence instead of learned skills. They can also be unfair for students from different language backgrounds, cultures, or learning styles, and they often fail to measure creativity, problem-solving, or real-world ability. For the update, if we “parse” or break down a standardized test, we see that it usually includes multiple-choice questions, reading passages, math problems, and sometimes short written answers. The test is given the same way to every student, with the same timing, instructions, and scoring rules. For example, a typical state reading exam gives students a set amount of time to read several passages and answer questions that test comprehension, vocabulary, and analysis. The strength of this testing method is that it produces results that are easy to compare across schools and groups, offers clear scoring guidelines, and helps highlight strengths and weaknesses in instruction. However, a major weakness is that standardized tests cannot capture everything a student knows or can do, especially skills like creativity, collaboration, or critical thinking. They may also disadvantage students with test anxiety or those who do not perform well under timed conditions. In practice, standardized tests offer useful data—but only when used together with other forms of assessment, not as the only measure of student ability or success.

When Standardized Tests Are at Their Best and Worst

Standardized tests work best when they are used to provide a clear and consistent picture of how students are performing across different schools, regions, or grade levels. Because everyone takes the same test under the same conditions, the results help identify broad learning trends and guide decisions about curriculum, teaching strategies, and resource allocation. At their worst, however, standardized tests reduce learning to numbers and rankings. They can create pressure that leads to teaching the test instead of nurturing deeper understanding, creativity, or problem-solving. These tests may also disadvantage learners who experience anxiety, lack resources, or come from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, making the results less representative of their true abilities.

A good example of how a standardized test is implemented is the Stanford Achievement Test (SAT-10). In practice, students take the test on the same day with the same instructions, time limits, and materials, ensuring that all conditions are equal. Their answers are scored through automated systems, and results are compared to a national sample to determine how each student performs relative to others. This process gives schools reliable data about strengths and gaps in areas like reading or math. However, while standardized tests offer fairness and large-scale insights, they also have weaknesses. They measure only a narrow slice of learning and may not capture skills such as creativity, collaboration, or real-life problem-solving. They can also be stressful for children and may reflect differences in background more than differences in ability. Because of these limits, standardized tests are most meaningful when used alongside other forms of assessment that show the whole child.

When Standardized Tests Are at Their Best and Worst

Standardized tests work best when they are used to provide a clear and consistent picture of how students are performing across different schools, regions, or grade levels. Because everyone takes the same test under the same conditions, the results help identify broad learning trends and guide decisions about curriculum, teaching strategies, and resource allocation. At their worst, however, standardized tests reduce learning to numbers and rankings. They can create pressure that leads to teaching the test instead of nurturing deeper understanding, creativity, or problem-solving. These tests may also disadvantage learners who experience anxiety, lack resources, or come from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, making the results less representative of their true abilities.

A good example of how a standardized test is implemented is the Stanford Achievement Test (SAT-10). In practice, students take the test on the same day with the same instructions, time limits, and materials, ensuring that all conditions are equal. Their answers are scored through automated systems, and results are compared to a national sample to determine how each student performs relative to others. This process gives schools reliable data about strengths and gaps in areas like reading or math. However, while standardized tests offer fairness and large-scale insights, they also have weaknesses. They measure only a narrow slice of learning and may not capture skills such as creativity, collaboration, or real-life problem-solving. They can also be stressful for children and may reflect differences in background more than differences in ability. Because of these limits, standardized tests are most meaningful when used alongside other forms of assessment that show the whole child.

When used to fairly, consistently, and objectively measure large-scale learning outcomes, standardized tests perform at their best. These tests are helpful for comparing performance across schools, regions, or populations because every student responds to the same questions under the same circumstances. They work particularly well for evaluating fundamental abilities like reading, math, and foundational knowledge that can be quantified by right or wrong responses. Additionally, standardized tests are effective when used in conjunction with teacher evaluations, projects, and classroom performance as part of a larger assessment system. In these cases, they provide valuable data without being the sole basis for major decisions.

However, when they are overused or viewed as the sole indicator of a student's aptitude or a teacher's efficacy, standardized tests are at their worst. They often fail to capture complex skills like creativity, collaboration, critical thinking, communication, and real-world problem-solving. These tests can also disadvantage students who struggle with test anxiety, time pressure, or language barriers, even if they understand the content. When high-stakes consequences—such as grade retention, scholarships, or school funding—depend heavily on standardized test scores, the system can create stress, narrow the curriculum, and encourage “teaching to the test” instead of promoting meaningful learning. To put it briefly, standardized tests are most beneficial when they are used carefully and sparingly, and they are least effective when they take over the educational process or disregard the variety of strengths that students possess.

Standardized tests are at their best when they provide objective, consistent data about student learning and allow fair comparisons across large groups. They are most useful for measuring broad academic outcomes and ensuring that all students are assessed under the same conditions. However, they are at their worst when used for high-stakes decisions, such as judging teachers, ranking schools, or labeling students, because these uses can create pressure, encourage teaching to the test, and disadvantage learners with different backgrounds. In practice, a standardized test is developed by aligning questions with specific competencies, piloting them for fairness, and administering the test under uniform rules so everyone has the same instructions and time limits. This process makes standardized tests reliable and efficient, but their weaknesses include limited measurement of creativity or real-world skills and the potential for cultural bias.

Parsing a Standardized Test in Practice

For this update, I examined how the National Achievement Test (NAT) is implemented in Philippine schools. The NAT is a nationwide standardized assessment given to specific grade levels to measure students’ mastery of key learning areas. It follows a fixed format, uses multiple-choice items, and is administered under strict testing conditions to ensure consistency across schools.

One strength of the NAT is that it provides reliable, large-scale data that helps DepEd identify learning gaps and monitor overall educational performance. It also guides schools in improving instruction based on competency trends. However, its weaknesses include test anxiety among learners, the risk of teaching “to the test,” and the limited scope of multiple-choice items, which may not fully capture higher-order thinking or real-world skills.

Standardized tests are most valuable when they gather broad, objective data that guide large scale decisions and reveal important educational trends. For example, nationwide assessments like the National Achievement Test (NAT) help policymakers identify which regions or grade levels need stronger support and better resources. However, standardized test are at their worst when they are treated as the sole measure of students's worth, a learner's potential, or a school's overall quality. Relying too heavily on test scores overlooks the richness of individual learning styles, the influence of home and community environments, and the unequal access to educational opportunities that shape student performance.

Standardized tests are at their best when they are used to provide reliable, comparable data about large groups of students, monitor system-wide progress, and identify broad patterns in learning. They work well when carefully aligned to curriculum standards, administered fairly, and interpreted as one piece of a larger assessment picture. However, they are at their worst when used as high-stakes tools to label students, determine teacher effectiveness, or make major placement decisions. Overreliance on standardized tests can disadvantage students with disabilities, English learners, and those from marginalized backgrounds, while narrowing curriculum and creating stress for both students and teachers.

A standardized test is basically a uniform exam that tries to measure everyone’s skills the same way, at the same time, with the same scoring rules. In practice, experts design the questions, test them on sample groups, refine anything that seems unfair or confusing, and then roll the final version out under tightly controlled conditions. This makes the results easy to compare across students and schools, and it’s efficient for evaluating big groups quickly. But standardized tests also have real limits—they focus on a narrow band of skills, can favor students with more resources or test-taking experience, and often add pressure that doesn’t reflect someone’s true ability. They’re helpful tools, just not the whole picture of what a person knows or can do.

A standardized test is basically a uniform exam that tries to measure everyone’s skills the same way, at the same time, with the same scoring rules. In practice, experts design the questions, test them on sample groups, refine anything that seems unfair or confusing, and then roll the final version out under tightly controlled conditions. This makes the results easy to compare across students and schools, and it’s efficient for evaluating big groups quickly. But standardized tests also have real limits—they focus on a narrow band of skills, can favor students with more resources or test-taking experience, and often add pressure that doesn’t reflect someone’s true ability. They’re helpful tools, just not the whole picture of what a person knows or can do.