Multimodal Literacies MOOC’s Updates

Media Relativity: A Picture is Not Always Worth a 1,000 Words

I believe that every age, perhaps except the first age of humankind or what most of us think to be humankind (which basically translates into a conceptualization and image people who act, think, and look like ourselves) suffers from Chronological Snobbery: we inevitable play the role of the armchair quarterback and suppose that we have advanced humankind and made significant, better, and even more progress than the ages before us. One needs only to turn to colonization, the mission of the Jesuits in the “New World,” Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, the Industrial Revolution, Manifest Destiny, the so-called advancements in the medical sciences such as “safe” abortions or genetic engineering to justify and support this view.

However, to a degree, most all of life issues—from the philosophical to the practical—are relative: simply reflect on how many Supreme Court decisions come down to definitions . . . of right/s, of life, of violations, of freedom to practice religion, and of freedom of speech. Is there really a literal definition of life, for example? Certainly, many doctors and scientists think so, as do many Evangelical Christians, but the issue is that often these groups’ definition are, or can at least be reasonably interpreted as, mutually exclusive, yet they are often not, not always.

It depends on one’s (and on the particular group with which one primarily identifies) perspective, self-reflection, and critical questioning. Without appreciating or engaging in these three human “conditions,” one will almost always fall into the trap of Chronological Snobbery, which is a concept that comes to mind every time I think of C.S. Lewis. In many of his works, the seminal Lewis scholar, Art Lindsley recounts that Lewis defines this form of egotism as “the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate of our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that count discredited.” One might think that Lewis is simply rejecting the truly relatively modern ideas, ideals, beliefs, practices, intuitions, etc. of the current time. In reality, he spoke and wrote about his own rejection of Christianity due to Chronological Snobbery, which in turn was based on his belief that something so ancient our outdated could have any to value him and to his modernity.

Nevertheless, as referenced, the idea of contextual egotism still holds strong, with each age thinking that it has improved a particular aspect of the human condition, whether medical, educational, social, political, or otherwise, and it here that I finally arrive at this week’s update topic. Multimodal literacy, which I firmly believe adds richness to the nuanced, yet worldly social practices of knowledge- and meaning-making, should not go without “uncritical acceptance,” which in turn is what I appreciate about this week’s lessons and about the work of Gunther Kress, Roland Barthes, Nancy Duarte, Richard E. Mayer, and Ruth Clark. Each has written about multimodal literacies in one way or another, but it is the work of Mayer (as an editor and sole author) on which I will concentrate.

In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (2005; 2014), editor and author of numerous chapters, Richard E. Mayer defines multimedia as presenting both words (such as spoken or printed text) and pictures (such as illustrations, photos, animation, or video)” (2). He continues to write that by words, I mean that the material is presented in verbal form, such as using printed text or spoken text. By pictures, I mean that the material is presented in pictorial form, such as using static graphics, including illustrations, graphs, diagrams, maps, or photos, or using dynamic graphics including animation or video. (2)

Similarly, multimedia learning is conceptualized as “building mental representations from words and pictures . . . when learners are able to build meaningful connections between visual and verbal representations” (2; 5). In short, the presentation of, and learning from, material in two or more forms is multimedia.

A major theme of the anthology is that “[w]hen words and pictures are presented together as in a narrated animation” students learn more meaningfully (3), and a guiding motif of the work is that in “light of the power of computer graphics [which can be expanded to “computer technologies”], it may be useful to ask whether it is time to expand instructional messages beyond the purely verbal” (3-4). These claims inform every chapter of the work, and especially those chapters written by Mayer, but they also fall in line with those of Gunther Kress, who as Kalantzis and Cope note, “has characterized this [i.e, the “phenomenon of multimodality”] as the rise of the image culture, displacing at least to some degree an earlier modern culture dominated by [verbal] language and literacy” (17).

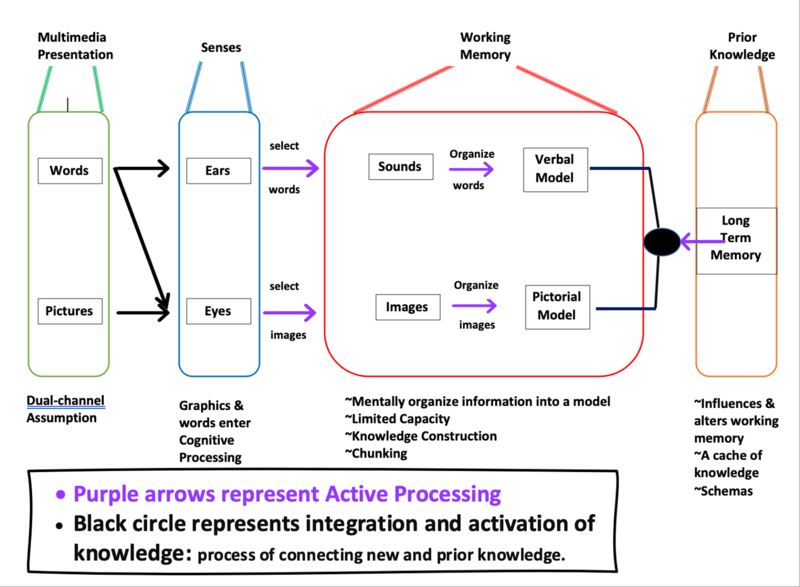

This displacement is disruptive but does not have to be problematic. That is, one can study and thereby appreciate multimedia knowledge- and meaning-making if one critically, as Lewis might remind us, considers the characteristics of the multimedia environments from a cognitive multimodal perspective. Part of this critical assessment is the realization of “how the mind works – namely, that the human mind is a dual-channel, limited capacity, active-processing system” (Mayer 37). This processing of words and pictures can be represented as follows:

It is important to note that Mayer and other authors featured in the anthology do not treat verbal and pictorial forms as completely separate entities, with entirely different grammars and affordances—a practice that even Kress and van Leeuwen concede they somewhat do in Reading Images; they acknowledge that they “stand with one foot in the world of monomodal disciplines,” yet their work was published well before digitization and advanced computer technologies were realized. However, now, we are in such a world, but we must not blindly accept it just as fact but must realize, as Kalantzis and Cope do in their body of work, that the past informs the present . . . that one cannot separate the ages with solid black and white lines and that just because we think we are better, we are not always better off. Likewise, we should not discredit an idea, approach, practice, phenomenon, or otherwise simply because it is “new.”

As human agents of change, much like multimedia (except for the human aspect—although the lines are becoming more blurred), we are translators of the “old,” constructing new versions and new meanings, to varying degrees, that connect and converge, that are familiar and foreign, and that are unique and shared.

What is old is often refashioned as new, and what is new will eventually become old, and this old will inform the contemporary, newer versions, and the cycle will continue. As Kress demonstrates in his own body of work, multimodal literacy and learning are not new but computer-mediated environments and apps and the modal and social convergences they inspire are, to a degree that is! Therefore, as long as we engage in a healthy amount of Chronological Snobbery, i.e., appreciating multimedia literacies while also critically acknowledging their traces, we should move forward or onward.

Works Cited and Referenced:

Kalantzis and Cope. Regimes of Literacy. https://d1311w59cs7lwz.cloudfront.net/attachment/91492/6676caca33e915e42dea2d3d138c3698 https://rb.gy/przdsw

Kress and van Leeuwen: https://newlearningonline.com/literacies/chapter-8/kress-and-van-leeuwen-on-multimodality.

Lindsley, Art. “C.S. Lewis on Chronological Snobbery.” https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/webfm_send/47.

Mayer, Richard E. The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. https://www.amazon.com/Cambridge-Handbook-Multimedia-Handbooks-Psychology/dp/1107610311/ref=sr_1_2?dchild=1&keywords=multimedia+learning&qid=1597876937&sr=8-2.