Learning, Knowledge and Human Development MOOC’s Updates

Discussion Forum: Essential Update #2 - June 21, 2024: Understanding “Social Mind” through Examples of Individual Skill Development in Different Social Situations

Option #2:

The concept of “social mind” advanced by social cognitivists like James Paul Gee, Jean Lave, Etienne Wenger and Lev Vygotsky treats the individual human mind – with all its biological (“natural”) cognitive affordances – as a (“nurtured”) function of the social environment and interactions it has with others.

In many ways, this concept is a theorization of something very commonsensical – just think: how would David, a tenth grader, know to turn the panging phrase “I love you” in his head every time his romantic interest Delilah passes by had it not been for his exposure to the English language through social situations like listening to his family talking in the early stages of his cognitive development and later through the English media and his language classes. In fact, it may have been these very English classes where he first met Delilah and developed feelings for her after the many interactions they had, say, on the poet Robert Browning, which in the first place made our hopeless romantic David think “inside his head” that he likes Delilah a bit more than a friend. Moreover, when sitting alone David daydreams about growing old with Delilah, his thoughts may very well be under the cultural influence of Browning’s lines “Grow old with me/The Best is yet to be/The last of life for which the first was made” that they had discussed in class during the previous term. Thus, the prerequisites for thinking all alone if often a necessary communion with the other, exposure to shared symbolic tools like language that supports imaginative and abstract thinking and access to existing cultural texts to refine and assimilate one’s thoughts all of which most definitely makes such a moment of thinking a social affair.

Now suppose David grew up in a society where romantic love was perceived as a moral failure. After having grown up with such cultural perceptions for years, when he first reads the lines “The last of life for which the first was made”, to him it would probably mean little more than pure and vile decadence. Resultantly, he would find it very difficult to grasp the beauty of the words and will likely fail to adequately analyze such lines in his class assessments, unless his instructor arranges remedial classes – something that he may never even have required had the disdain for romantic love not been so deep-seated in him. Furthermore, freely interacting with the opposite sex might be considered as such a taboo in his society that when Delilah tries to help David with the Robert Browning lessons, he might shy away, thus losing both the opportunity of learning from a competent peer as well as developing any meaningful relationship with them. This shows that the principles of the community in which one grows up and its associated culture can have long-standing effects on an individual’s learning.

Curiously enough, the concept of “social mind” is relevant even when the focus is solely on an individual’s skill development, even though it might immediately seem to have nothing to do with socialization as such. Here, I would use my experience of taking swimming classes for the very first time for further elaboration.

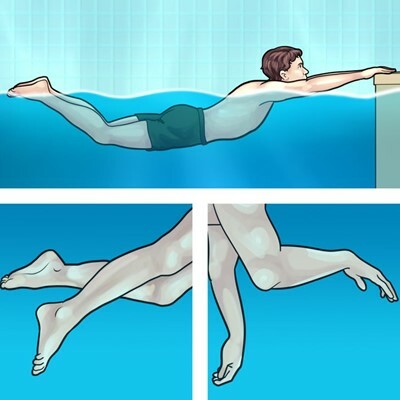

When I opened Harry Hazlehurst’s How to Teach Yourself to Swim (Hazlehurst 1970), swimming, I assumed, would be a solitary endeavour. The book, in fact, claimed “Confidence is 75% of the art of swimming. Relaxation, proper breathing and the movements comprising the stroke complete the formula” (5) Yet, when I stepped into the pool for the first time, with children more than 10 years younger than me fabulously swimming about the area, I had no idea how I would acquire even one of the components of the aforementioned formula. Needless to say, I registered for a trainer. But even after she asked me to stand near the vertical metallic bars and set my body afloat to paddle, all I could do was to let my legs go only for one of them to fall immediately on the floor to cushion me with safety. The trainer, meanwhile, asked me to keep trying and disappeared.

After an eternity of fumbling, a second grader boy approached me and repeatedly demonstrated to me how to go about it. But for me, the boy seemed too much of an expert to be deemed as a point of reference. However, soon another older girl, who was paddling beside us told me that it is natural for the feet to go down initially. While that didn’t quite teach me how to set myself a float, I at least realized there was hope. The girl’s relative proximity to my age too helped. In fact, soon I started spotting women older than myself struggling to keep themselves afloat, yet trying nonetheless. This exposure and interaction with my peers having varying levels of competencies helped me keep at the activity with me mentally thinking about how buoyancy works along with many rounds of trial and error until I finally figured out how to paddle holding on to the bars, with confidence. Likewise, I am sure demonstrating to a newcomer a skill that they had already acquired must have equally boosted the confidence of my young and helpful peers.

It was then that the trainer came in once more, as if she was waiting for me to get to this stage, to refine my posture further. Ever since, my swimming lessons have proceeded in this manner making me realize that while every little swimming skill that I acquired must definitely be informed by my cognitive ability to grasp my trainer’s instructions (i.e. my individual mind), this cognition was “distributed” amongst my peers, wherein, it was through the instructions given by my trainer as well as my observations of and interactions with of my fellow swimmers that I was able to holistically understand how to maneuver each part of my body. It was my own “peripheral legitimate participation” (theorized by Jean Lave and Etienne Wenger as communities of practice) as a newcomer into a group of swimmers from diverse backgrounds and age groups whose presence helped me assess my own competence which in turn secured my sense of identity as a swimmer and certainly did the same for my peers to in manners discussed previously. It was this collaborative learning experience that our trainer, hierarchically situated above us, made space for by disappearing and reappearing at the opportune moments that played a crucial role in building the confidence that Hazlehurst had claimed was “75% of the art of swimming”.

References:

Erickson, M., Hosmer, S. K., Scanlan, M. 2023. “Etienne Wenger: A Social Learning Theorist.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Educational Thinkers, ed. B. A. Geier, 1-13. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hazlehurst, Harry. 1970. How to Teach Yourself to Swim. USA: Haldeman-Julius Publishing Company.

“How to Float for Beginning Swimmers.” Published on YouTube by decathlon_india (Accessed on June 21, 2024). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FowMLjXIVag&list=PLfkzmdGbn1iX8RdW1-WbmS7sypqk3yg0L&index=4

“Jean Lave.” Published on Pedagogy For Change (Accessed on June 21, 2024). https://www.pedagogy4change.org/jean-lave/

Mcleod, Saul. 2024. “Vygotsky’s Theory of Cognitive Development.” Published on Simply Psychology (Accessed on June 21, 2024). https://www.simplypsychology.org/vygotsky.html

Paul Gee, James. 1992. The Social Mind: Language, Ideology, and Social Practice. New York: Bergin and Garvey.

@Sragdharamalini Das,