FA16 Immunization Module’s Updates

DNA Vaccinations

As one of the topics we could cover was new vaccination technology, I took this as an opportunity to discuss DNA vaccines. The main types of vaccine that we have talked about are live attenuated and inactivated vaccines, both of which attempt to exploit the body’s natural adaptive immune response. While live attenuated vaccines introduce a weaker form of the pathogen into the system, the target virus or bacterium still has to grow within the person to incite the long-lasting response. This means it can still pose a threat to people with weak or compromised immune systems, making it difficult to use them on patients of already struggling health(1). While inactivated vaccines do not pose this same threat they do not proliferate within the person and thusly do not incite the same, lasting response, requiring boosters and re-administration in order to remain helpful. These downfalls are where DNA vaccines could prove to be a great advance in the vaccinated future.

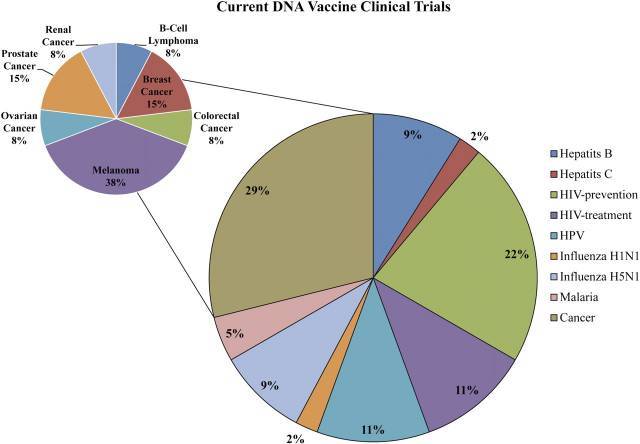

This idea was popularized in the late 20th century when it was discovered that injection of plasmid DNA could cause an antibody response to antigen, and thus was born underlying concept of the DNA vaccine (3). When the genetic material is introduced into the host some cells will uptake it and produce the protein products of those genes, the expression of which on MHC I and II then causes immunologic host response [Figure 2] (5). DNA vaccines then have the potential to cause in vivo expression of the antigens, but do not do so by actual pathogen proliferation and growth(4). Unlike live attenuated vaccines which still have the power to proliferate, and inactivated vaccines that lack the ability to cause lasting immune response, DNA vaccines have the potential to cause long term immunity within a subject without subjecting them to the live pathogen. While early trials experienced difficulty in inciting any real response, new delivery approaches such as needle free and electroporation, along with the use of aids like adjuvants, have given research renewed attention in recent years. In 2011, 43 clinical trials were being conducted with DNA vaccines, the majority investigating HIV and cancers [Figure 1](3). With expanded research and new vaccination methods, it is possible that DNA vaccines may become the safe and effective alternative to live attenuated and inactivated vaccines in the future.

Sources

1) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rb7TVW77ZCs

2) “Principles of Vaccines” PDF

3) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3202319/

4) http://content.ebscohost.com.proxy2.library.illinois.edu/ContentServer.asp?T=P&P=AN&K=118113295&S=R&D=a9h&EbscoContent=dGJyMNLr40SeqLU40dvuOLCmr06eqLBSsK24SrCWxWXS&ContentCustomer=dGJyMPGut1C3rLZNuePfgeyx44Hy7fEA

5) http://biology.kenyon.edu/slonc/bio38/scuderi/partii.html

Sounds like a promising option for the future.

This seems like it would be a very good approach for antigens that are difficult to produce/store/isolate in vitro. More difficult, that is, than storing/isolating/delivering the DNA, which is a task in itself. But, it seems promising.

I agree with @Saadiya in wondering about the side effects. Do DNA immunizations avoid the inflammatory effects of live attenuated vaccines since it is not a pathogen injection? The idea of using DNA to cause in vivo antigen expression instead of introducing pathogen into the body is compelling and sounds much safer. But have there been studies done comparing the effectiveness and life span (amount of time the vaccine is effective) of the DNA vs pathogen containing immunizations?

These DNA vaccines seem to sound promising, but are there any side effects, with regard to gene expression, that we need to worry about?