Meaning Patterns’s Updates

On the Differences beween Speech and Writing

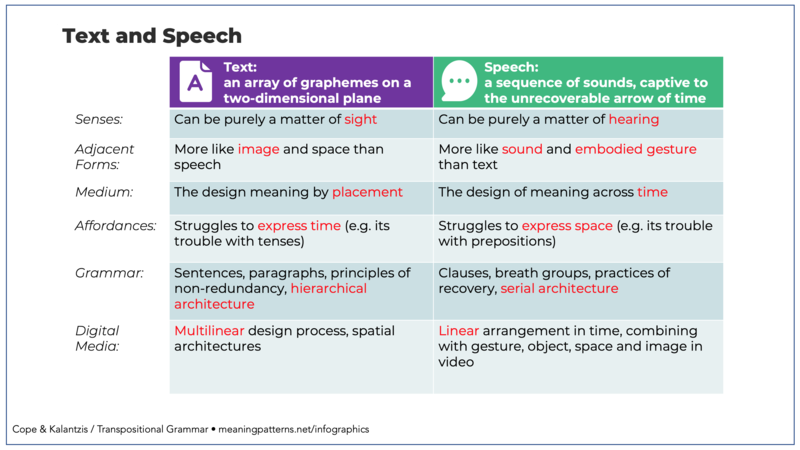

Speech and writing are different in the very processes of their representation and communication. Their grammars, M.A.K. Halliday§0.3a says, are fundamentally different. Speech, he says, strings information units one after the other, connecting them with words that link roughly equivalent things (such as “and,” “or,” “then”) and logical connectives that link things where a difference needs to be highlighted (such as “until,” “as,” “to,” “because,” “if,” “to,” “which”).

Writing, on the other hand, uses nominalization, packing an idea that might have been a whole spoken clause into a noun or a noun phrase inside a written clause. “People should be able to bring” in an oral text about opportunities to bring their capacities to a task, becomes “provides an outlet” in the written text. Writing performs the logical task of connecting ideas in a way quite different from speaking. Each is just as intricate as a meaning-design. It is just that they are very different kinds of intricacy. They are different ways of seeing the world and thinking about the world.

There are also characteristic differences in the orientations of meaning-makers to the world. Speaking is full of statements like “I think,” “in my opinion,” “I’m sure,” “you see?,” and “you know?” which make the interactive stance of the participants more visible than is mostly the case for writing. Speech will more often use the active voice, in which who is doing what to whom is directly stated. (“I went to the party yesterday, and I found it interesting to meet lots of new people.”) In these and other ways, speaking makes the interest-laden role of the speaker more explicit.

A writer, on the other hand, is more likely to choose the passive voice, and is also more likely to choose third person to refer to events. The writer may be referring to the same thing as a speaker, but writers tend to create the impression that objects and events have a life of their own. (“Yesterday’s party was well attended, with many new faces.”) This is how writing has an aura of objectivity while speaking has an aura of subjectivity. Writing, explains Halliday, is inclined to represent the world more as a product; speaking more as a process. Speech is more spun out, flowing, choreographic, and oriented to events (doing, happening, sensing, saying, being). It is more process-like, with meanings related serially. Writing is dense, structured, crystalline, and oriented towards things (entities, objectified processes). It is product-like and tight, with meanings related as components.40

Of course, when writing has this aura of objectivity, this is more a matter of rhetorical effect,§AS2.1 an impression you are expected to get, rather than an intrinsic reality. Information writers may want you to think that they are speaking facts or expert argument, though just to be writing they must have a lot invested personally and subjectively. Speakers, by comparison, are mostly more explicit about their subjective, immediate, here-and-now connection with their meanings. “You know, I reckon …, ” they might characteristically say when they frame a statement. When the speaker is in the presence of the listener, it is hard for them not to make explicit their personal investment in what they are saying.

There are also important differences in the ways speaking and writing make reference and point to context. In oral conversation, “I” or “you,” “this” or “that,” “here” or “there,” “today” or “yesterday” are all relative to the speaking participants, their time, and their place. In terms of our classification of functions, oral meaning is carried by context. Writing, however, first has to name “I”, “you,” “this,” “that,” “here,” “there,” “today,” and “yesterday” before these words can be used. In terms of our classification of functions, written meaning is carried to greater extent by structure, or internal reference, than by context, or external reference.41

Then there are other fundamental differences in the manner of construction of speech and writing, which in practical ways determine their architecture. Speech is full of repetitions and errors that are corrected audibly and on-the-fly. A writer removes repetitions and erases errors visually. Speech is linear because sound is rendered in time, clause stitched onto preceding clause, one stitch at a time. Writing is multilinear because it is rendered visually. “She” refers to a woman named some place earlier in the text, and multiple “she”s point back to the same reference – visualize pronoun references as lines across the text, and you will see the multilinearity.

Hierarchical information architectures are created in written text by clauses that are nested into sentences into paragraphs into sections into parts or articles into books or magazines. These are explicitly marked in an essentially visual arrangement. The logical structures of information texts, arguments, and narratives can also be diagrammed demonstrating that they too do not simply work in linear and sequential ways. These are some of the underlying reasons why writers keep writing over text, backwards and forwards, eliminating redundancy, refining the logic of their text by revising the spatial presentation of their meaning.

Planning is followed by drafting and editing. Visual arrangement takes priority over the sequence of text-making actions. If writing were to be like speaking, the reader would replay the writer’s keystrokes, revealing the hesitations and the changes. This would get in the way of communication, and surely the writer would not want the distracting messiness of their interim thinking to be made visible. Writing is carefully arranged in a visual form across the canvas of space, where speech is sound, tied to the arrow of time.

Today, the multilinear and visual processes of text construction are intensified by digitization, affording writers the infinite flexibility and efficiencies of being able to work back over text without having to rekey a single character unnecessarily. Written digital text is more visual and more framed by multilinear processes of construction than ever. It is more different from speaking than ever.

Now, something has crept up on us in the drift of this argument. In this grammar we’re not going to need to talk about a thing called “language” that crosses speech and writing. In fact, to speak of language is to conflate some crucial distinctions – distinctions that are all-the-more important in the era of digital media. You’ll hear almost nothing of language for the rest of this book, and the one that follows.

- Cope, Bill and Mary Kalantzis, 2020, Making Sense: Reference, Agency and Structure in a Grammar of Multimodal Meaning, Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 30-33. [§ markers are cross-references to other sections in this book and the companion volume (AS); footnotes are in this book.]

The argument is expanded upon in this chapter.

Getting rich-more powerful and famous? JOINING THE GREATORLDRADO OCCULT BRINGS YOU INTO THE LIMELIGHT OF THE WORLD IN WHICH YOU LIVE IN TODAY. YOUR FINANCIAL DIFFICULTIES ARE BROUGHT TO AN END. WE SUPPORT YOU BOTH FINANCIALLY AND MATERIALLY TO ENSURE YOU LIVE A COMFORTABLE LIFE. IT DOES NOT MATTER WHICH PART OF THE WORLD YOU LIVE IN. FROM THE UNITED STATES DOWN TO THE MOST REMOTE PART OF THE EARTH, WE BRING YOU ALL YOU WANT. BEING AN GREATORLDRADO BROTHERHOOD MEMBER WE GUARANTEE YOU BEING A MILLIONAIRE BETWEEN TODAY AND THE NEXT TWO WEEKS. YOU BEING IN THIS OUR OFFICIAL PAGE TODAY SIGNIFIES THAT IT WAS ORDERED AND ARRANGED BY THE GREAT LUCIFER THAT FROM NOW ON, YOU ARE ABOUT TO BE THAT REAL AND INDEPENDENT HUMAN YOU HAVE ALWAYS WISHED YOU WERE . Or contact us on WhatsApp:+233274691762

DO YOU WANT TO JOIN OCCULT TO BE NATURALLY RICH JOIN MONEY RITUAL +2349827025197 OCCULT FOR WEALTH AND FAME JOIN OCCULT MEMBERS TO MAKE MONEY JOIN SECRET OCCULT KINGDOM TO BE RICH AND POWERFUL HOW TO JOIN OCCULT FOR INSTANT RICHES HOW TO JOIN SECRET SOCIETY TO BE RICH WITHOUT KILLINGS YOU WANT TO JOIN MONEY MAKING OCCULT FOR FINANCIAL SUPPORT OR FINANCIAL FREEDOM TO BE FREE FROM POVERTY TODAY AND BECOME RICH CONTACT THE TEMPLE NOW WITH +2349027025197 DON’T THINK THAT ALL YOUR HOPE ARE LOST IN THIS WORLD YOU STILL HAVE THE ABILITY TO MAKE A GOOD LIVING BY JOINING MONEY RITUAL SECRET OCCULT THAT WILL MAKE YOU VERY RICH WITHOUT KILLING ANY HUMAN BEING TAKE THIS DECISION TODAY AND CHANGE YOUR WORLD TO A BETTER ONE WE THE Guru Maharaj Ji BROTHERHOOD OCCULT MEMBERS ARE READY TO HELP YOU AS LONG AS YOU ACCEPT TO MAKE A RITUAL SACRIFICE TO OUR LORD SPIRITUAL TO BECOME ONE OF US THEN YOU ARE READY TO BOOST YOUR CAREER AND BE A GREAT MAN WITHOUT BEING AFRAID OF ANY LIVING THINGS IN THIS WORD JOIN US TODAY

I want to join occult for money ritual +23427025197 how to join occult for ritual money I want to be a great politician I want to be a great man I want to be the richest I want to be a great businessman I want to be doing miracles I want to be a great pastor to know how to get all these rich power rotation I want to join occult in Nigeria I want to join occult in Ghana I want to join occult in Cameroon I want to join occult in South Africa there is no blood shared if you’ve been accepted to join this organisation you are to pay the price at the age of 85 years you sacrifice yourself to the lord Lucifer this simply means that you are going to die at the age of 80 years you can reach us on WhatsApp or contact of the Grandmaster of GREATORLDRADO BROTHERHOOD OCCULT CALL +2349027025197 if you want to see more https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLtCGX9fymO857gGFq4lKQE4lD0SYSosA9&feature=shared

Getting rich-more powerful and famous? JOINING THE GREATORLDRADO OCCULT BRINGS YOU INTO THE LIMELIGHT OF THE WORLD IN WHICH YOU LIVE IN TODAY. YOUR FINANCIAL DIFFICULTIES ARE BROUGHT TO AN END. WE SUPPORT YOU BOTH FINANCIALLY AND MATERIALLY TO ENSURE YOU LIVE A COMFORTABLE LIFE. IT DOES NOT MATTER WHICH PART OF THE WORLD YOU LIVE IN. FROM THE UNITED STATES DOWN TO THE MOST REMOTE PART OF THE EARTH, WE BRING YOU ALL YOU WANT. BEING AN GREATORLDRADO BROTHERHOOD MEMBER WE GUARANTEE YOU BEING A MILLIONAIRE BETWEEN TODAY AND THE NEXT TWO WEEKS. YOU BEING IN THIS OUR OFFICIAL PAGE TODAY SIGNIFIES THAT IT WAS ORDERED AND ARRANGED BY THE GREAT LUCIFER THAT FROM NOW ON, YOU ARE ABOUT TO BE THAT REAL AND INDEPENDENT HUMAN YOU HAVE ALWAYS WISHED YOU WERE . Or contact this mobile:+2349027025197