Meaning Patterns’s Updates

"Mindsight:" Thinking Without Words

In image, the excess of the ideal arises experientially in the difference between seeing with the body’s eye (perceiving), and seeing with the mind’s eye (envisioning). Take the Eiffel Tower, says philosopher Colin McGinn in his book, Mindsight. If you are there, you can see it. But if you are not, you can envision it. “Seeing requires the presence of the object, while visualizing does not.”74

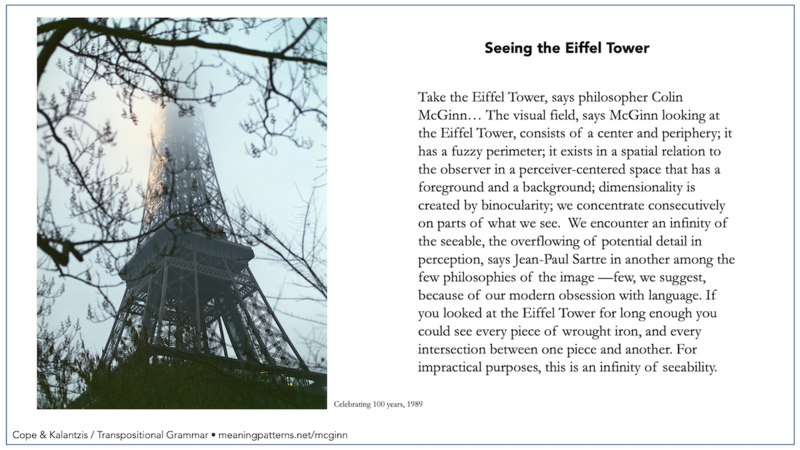

There are profound differences between perceiving and envisioning. In the form of image, this is the difference between encountering material structures of meaning, and figuring ideal structures. The visual field, says McGinn looking at the Eiffel Tower, consists of a center and periphery; it has a fuzzy perimeter; it exists in a spatial relation to the observer in a perceiver-centered space that has a foreground and a background; dimensionality is created by binocularity; we concentrate consecutively on parts of what we see.75 We encounter an infinity of the seeable, the overflowing of potential detail in perception, says Jean-Paul Sartre in another among the few philosophies of the image76 – few, we suggest, because of our modern obsession with language. If you looked at the Eiffel Tower for long enough you could see every piece of wrought iron, and every intersection between one piece and another. For impractical purposes, this is an infinity of seeability.

Envisioning, seeing the Eiffel Tower in one’s mind’s eye, is a completely different thing. The mental image is no longer saturated with an infinity of detail. We call to mind only the criterial features, the things that make the Eiffel Tower different from other agglomerations of wrought iron, or other tall things, like trees or mountains. Mental images are selective and abstracting. They desaturate the seeable world. Beyond the mental image, there is no more detail than that immediately called to mind. Much that could have been attended in perception is now unattendable.77

And another difference: “images can be willed but percepts cannot.” Mental images are reincarnated visual images, a metamorphosis of meaning that is creative and transformative.78 Sartre: envisioning is “shot through with creative will, a synthetic act of consciousness.”79 And Merleau-Ponty§AS1.4.3d on the kind of structures in such envisionings: these reflect “the intrinsic coherence of my representations.”80

John Locke§1.3a directed his philosophy to perception, where the structures of the material world determine the structures of our thinking. René Descartes directed his philosophy to envisioning, where the mind’s eye gives order to the material world. However, we need both these orientations, and Locke and Descartes§3.1.2g were each more nuanced than their caricatures usually allow.

Of course, despite their profound differences, direct perception and mental images are inextricably connected in the dialectical experience of everyday life. There is never one without it already having been the other. This, Sartre calls the “paradoxical simultaneity of percept and image,” seeing with the eye and seeing with the mind’s eye.81

The Eiffel Tower is recognizable when you see it in reality because the mind’s eye has captured its criterial form in previous experience, or the mediated social experience of pictures. “Tantamount to torture” is the meaning we bring to the images of the Abu Ghraib prison,§3.1.2a after we have seen them for the first time or when we see them again. Sartre again: “In perception, knowledge is formed slowly; in the [mental] image, knowledge is immediate.”82 Material structures and ideal structures of visual meaning are irrevocably interconnected, and in the dialectical play, the one always learning from the other. Experientially, however, they are profoundly different.

Though inseparable, the material can exceed the ideal, which is why we always need to keep looking – in the grammars of science, the humanities, arts, and politics. There is endlessly more to be seen in the infinity of the seeable. And the ideal exceeds the material. This Sartre calls “the imaginary,” a kind of “surpassing.”83 McGinn again: “cognitive imagination can outstrip sensory magination in its representational content ... Cognitive imagination takes us into alternative worlds ... The image liberate[s] the mind from the domination of perception.”84 Then there is the complicated dynamic of the picture, where someone has recreated the seeing for you, as if the naturalistic painting were truthful or the camera never lied. But this is an optical illusion, as full of visual tricks as it is also true. It is a series of trompe l’oeil, giving off the impression of being present, of virtually being there when in fact all you are seeing is a picture.§2.2c

The impression of knowing the Eiffel Tower or “tantamount to torture” even without seeing either tower or torture is another moment where the ideal exceeds the material, though our sociable and mostly trusting common sense assures us that the image, one way or another and however mediated, references material reality. The ideal structure of the image that stays in our mind’s eye, we trust, is connected to material structures of meaning.

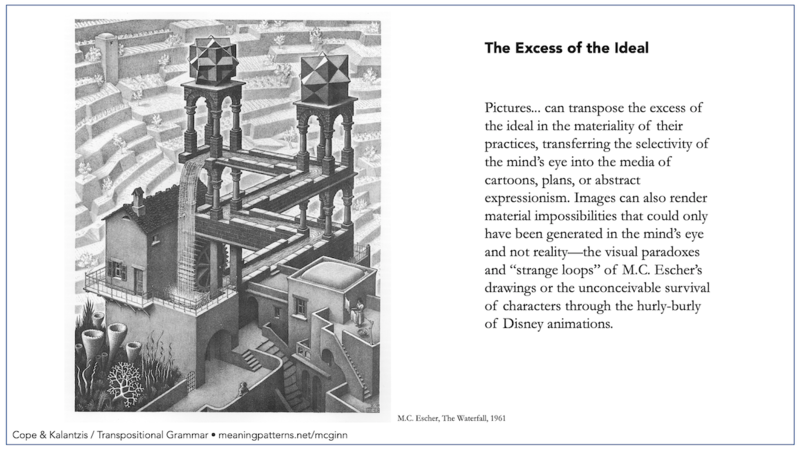

Pictures themselves can transpose the excess of the ideal in the materiality of their practices, transferring the selectivity of the mind’s eye into the media of cartoons, plans, or abstract expressionism. Images can also render material impossibilities that could only have been generated in the mind’s eye and not reality – the visual paradoxes and “strange loops”85 of M.C. Escher’s lithographs or the unconceivable survival of characters through the hurly-burly of Disney§AS2.5.1b animations.

From ordinary seeing and envisioning, McGinn went on to write about the human hand, and how “we are handlers by nature: we take hold, reach and grasp, seize, stroke, poke, squeeze, probe, and rub.” The anticipation of such meanings he calls “prehension,” not so unlike the way perception anticipates envisioning, while envisioning anticipates perception. The way we recognize the Eiffel Tower when we see it is from our previous experiences of seeing it or seeing images made by other people who have seen it. So it is with our hands. Our use of them creates meaning in our bodies and material objects. “We are great big hands extended toward the world around us.”86

Then this in 2011: McGinn, now aged 61, writes to a graduate student, Monica Morrison, aged 26. He says, “thank you, dearest I send you ... a hand squeeze.” Later he told her he “had a hand job imagining you giving me a hand job.”87 Just envisioning, he said, nothing had materialized, nothing that might be an object of perception in embodied reality. But the emails were real and for the student and the administration at the University of Miami. They amounted to sexual harassment, both student and administration said, so McGinn resigned.

- Cope, Bill and Mary Kalantzis, 2020, Making Sense: Reference, Agency and Structure in a Grammar of Multimodal Meaning, Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, pp.283-85 [§ markers are cross-references to other sections in this book and the companion volume (AS); footnotes are in this book.]